Technique behind the Theatre Organ part 2

Simplified description of the electro-pneumatic control/activation of the pipes (and other devices) in a theatre organ.

It should be remembered that these type of organs were mostly built early in the previous century at a time when electricity had just started to come into use (e.g. the telephone, trams and electric lighting). If people agreed to be connected up, a few lamps could even be supplied for free! Small motors and household electrical appliances had yet to be invented.

Organs had been around for a very long time, mainly for the ecclesiastical accompaniment of singing, insofar as that task was not reserved for a cantor.

Supplying the old organs with air using bellows and organ blowers was seen as a profession. The pipes were controlled mechanically from the keyboard using a wooden pull, push, or tilt movement to the air supply valves of the organ pipes.

Later the organ builders developed mechanical/pneumatic control systems where the keys passed on the command to the pipes via air currents and bellows. Air was already present and could therefore be used to ‘command’ the pipes from a distance. The old organs were slow and heavy to play but as people also sang slowly this was not a problem!

The invention of photography and later silent, black and white films, led to organs being modified and used for sound effects and entertainment.

This modification consisted of electrical control of the pipes via an electro-pneumatic system. The distance between the console and the organ could thus be bridged using a multi-core cable and the keys, as well as the stops that operate the registers, were fitted with switches. The console was given a different look and the number of organ pipe voices was expanded with drums, timpani, car horns, ship horns, a xylophone, and even a piano as well as chimes.

All this was set up in one or more organ rooms equipped with control valves to regulate the sound effect better. Until then the material used for organ building consisted mainly of wood, with tin, zinc or wood used for the pipes. Hinges and bellows were made of leather as were the nuts on primitive screw threads where adjustment was essential.

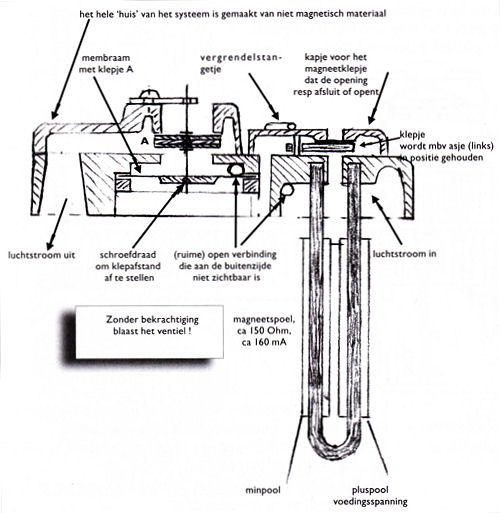

Everything that had to move was achieved by means of air, valves and bellows. Our forefathers were very resourceful! The application of electricity changed the method of transmission of the signals from the keys and pedals to the pipes and instruments. By means of electricity, a switch contact and an electromagnet, it was possible to create (or stop) an air flow and thus control an air valve via a bellows. This is sufficient to control the operation of a fully air-operated organ remotely.

The organist uses the register stop keys, which are arranged in a horseshoe shape above the keys of the console, to determine which voice, voices or instruments in the organ room will be addressed when the pedals or multiple keys are pressed.

This is achieved via an intermediate station called a relay centre. This contains one solenoid per register stop key. These send a small current of air to a bellows that in turn activates a wooden switch valve with many contacts. In this way the keys of the console are connected with the desired voice or voices. However, wooden switches can warp in the presence of humidity and temperature leading to poor contacts. As you can imagine, an organ relay centre that has been stored for a long time can keep various organ enthusiasts occupied for a long time!

The illustration above shows an electrically activated pneumatic valve ‘commanding’ a mighty pipe.

Source: NOFiteiten 2009

>> to Part 3